The Women in the Clouds: Writer Maryla Boutineau rediscovers female aeronauts from 1784-1945 who were almost lost to history

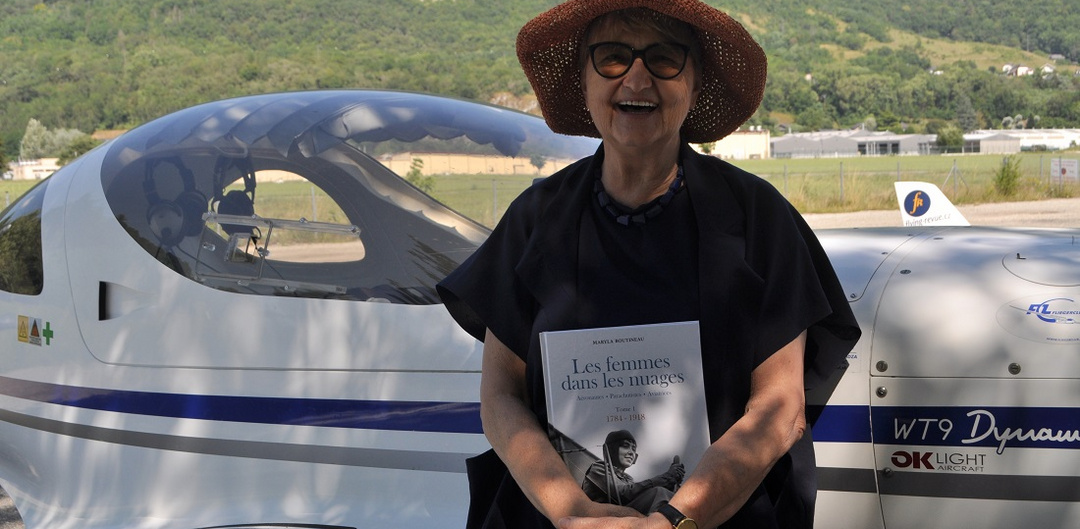

When meeting Maryla Boutineau, you find a thoughtful, warm person with a peaceful nature. Yet as you flick through the pages of her two volumes of ‘Les Femmes dans les Nuages’ (The Women in the Clouds) which tell the stories of the many women who contributed to the development of aviation, your mind boggles at the ferocious graft that she has thrown her mind and body into over the past three years, and you start to realise the passion that lies behind the calm exterior.

Rescuing stories

The two works on female aeronauts, parachutists and aviatrixes from 1784-1945 that Boutineau has lovingly – and obsessively – produced, are a one-stop-shop for anyone researching the concept of the female aviator and will no doubt become the go-to reference for historians, storytellers, filmmakers and indeed pilots of the future.

FAI strives to put Women with Wings into the limelight and anyone who has enjoyed articles from our series will have encountered some characters from Boutineau’s books already, such as Harriet Quimby and Baroness Raymonde de Laroche. Yet within the pages of these two books lie many new stories, ripe for rediscovery, of pioneering women from across the globe who each contributed to the development of aviation.

In the preface to volume two, historian and Secretary General of the Aero Club of France, Laurent Albaret, remarks:

"Boutineau does not stop at the biggest and most well-known names, but delves into history with a desire for completeness... The mass of documentation consulted in France and abroad, in public or private archives, the patient reading and the meticulous reviews of the press, demonstrate the author's desire […] not to forget any aviatrix who deserves the recognition of history."

PAINSTAKING Research

The books are currently available in French, but Boutineau herself is a multi-linguist, meaning that her works are especially broad in scope.

Originating from the former Czechoslovakia, she married a Frenchman and moved to Strasbourg, France, where she has lived most of her adult life. Not only has Boutineau spent hours perusing the pages of dusty French newspapers, but she has also delved into English and American archives, as well as sifting through volumes in Polish, Slovak and Cyrillic script, including from the former USSR.

Both books are neatly organised into chapters by country, and aside from French stories, also include tales of daring feats from USA, Germany, Argentina, Peru, New Zealand, Japan and many more besides. A veritable world of history waiting to be discovered. (Or should that be ‘her-story’?)

We meet on a hot day in the French aerodrome of Challes-les-Eaux – her brother Jiří Pruša has flown her to the meeting in his two-seater plane – and sit in the shade of a handsome chestnut tree to talk about the women who have looked down on Boutineau from the clouds, and requested that she tell their stories…

How was the research process, and how long did the first volume take to complete?

Two years – given my impatient nature, I could hardly have committed any more time to the project. I worked every single day, for up to 12 hours. I felt that the women in the clouds were impatiently waiting for me to finish!

What inspired you to commence your mission to share the stories of these pioneering female aviators?

It seemed to me that these female pioneers of aeronautics and aviation had been unfairly forgotten, so I wanted to give them justice. These young women, determined and courageous, had disappeared from our collective consciousness. I wanted to pay homage to them and bring their exploits back to life. And now I have done that, I realise that they have become role models for readers today, which brings me enormous pleasure.

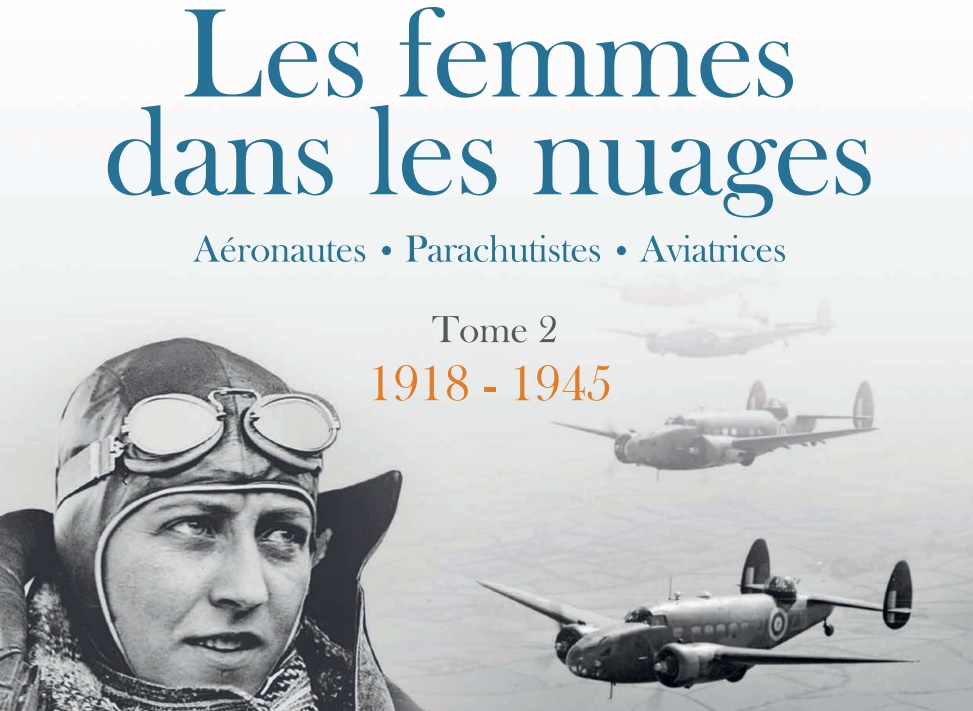

The cover of the second volume of Les Femmes dans les Nuages

Tell us about the research process, what resources did you find most useful, and was it hard to find pictures and details?

For the first volume, which covers the period from 1784 to 1918, I contacted numerous museums and received permission to use wonderful old photographs. All the contacts I made are thanked in my books. For the second volume (1918-1945) the period was of course, much more widely documented, so I was able to use Wikimedia commons and the publicly available images. I found that the Musée Air France had plentiful resources and were extremely helpful in the project.

When I didn’t have a photo for certain stories, or if the quality wasn’t good enough, I chose to draw my own illustrations, inspired by old photos. This work brought me particular pleasure, I enjoy drawing immensely.

I purchased many books myself, often autobiographical works, and sought out newspapers from the period: French, English, American, Russian, German, Italian and Polish. It was meticulous and very demanding work. Information for the period of 1784 – 1918 was often incorrect or vague, so I tried to find the original sources where possible – texts written by these 18th Century aeronauts themselves, or newspaper articles. For the 1918-1945 book, sources were more reliable. My aim with the books was to find, and share, the truth of each story.

Interestingly, I found that the families of my subjects were not always a good source of information. Their stories were so long ago, recent generations often hadn’t passed down their relations’ accomplishments. I hope that my work will help to give value to these families.

The Aero Club of France is highly supportive of Boutineau’s work and has contributed prefaces to both volumes, commending her on rediscovering aeronauts that had been completely lost to history, finding her research extremely thorough.

In the preface to the first book, Catherine Maunoury, President of Honour at the Aero-Club de France and double World Champion in Aerobatics, remarks that whilst these pilots "danced among clouds", they were certainly not “airheads”.

To become a pilot, then and now, you need to have your wits about you, and a technical understanding of the controls, procedures and mechanics of flight, something not necessarily part of a young woman’s education in previous centuries.

United in their courage

Did you discover that many of the women in your book were from similar backgrounds? Did they usually have family members who were also involved in aviation to support their endeavours?

The female aviators came from extremely varied backgrounds; some were from aristocratic families, others from upper middle classes. And of course, they weren’t all from rich backgrounds, some more penniless women had to work doing dangerous acrobatics on the wings of aeroplanes in order to get the cash to pay for lessons. Interestingly, there were many actresses among the best pilots! I also found milliners, chefs, musicians, shopworkers, who all had to earn extra income for long stretches of time in order to afford their lessons. Sometimes marrying into money helped them resolve their financial problems, but that was actually quite rare.

Some young women had pilot brothers who served as role models. They continued flying even if they lost their brother in an aviation accident. That kind of determination is unimaginable. Certain families supported their daughters’ wish to fly, but that wasn’t often the case; in aerodromes at that time, death reigned supreme. Pilot husbands sometimes encouraged their wives to take to the skies, but in other cases, they prevented them.

I found all sorts of scenarios, overall.

After having delved into their lives in such detail, do you think there is a common characteristic that is shared by a lot of female aviators?

Without doubt, their total determination. This helped them get back in the pilot’s seat after an accident and start flying again even after months in hospital. They lost friends, companions and lovers, but that wasn’t sufficient for them to abandon aviation.

They were hard on themselves and relentless against their rivals. Notably in the second generation, they took delight when they managed to beat the men!

During her research, Boutineau noticed a remarkable shift: as the years swept by and post-WWI women made their mark on the workforce, the focus for female pilots and parachutists became more competitive as they sought to beat their male equivalents. She notes that in the first generation it seemed that aviation was so new that no-one stopped to think that women couldn’t or shouldn’t become involved.

Not only did these aviators shed frilly petticoats and dresses to climb into the pilot’s seat, but they were also early adopters of other new trends, embracing the freedom of motor vehicles and practical clothing, rather than being bound by restrictive corsets and uncomfortable shoes. These were women who were ready to break out of the mould.

There’s a duality here. In aviation, knowing and sticking to rules and regulations is absolutely essential for safety. These women were determined enough to learn and respect these rules, but they also had an intrinsic desire to break others. They had the courage to bend the societal restrictions imposed on them in order to pursue their dream of freedom and flight.

Boutineau’s determination in researching these daring aeronauts reflects the willpower and sense of purpose that they all shared.

Although there won’t be another volume in the series, Boutineau is currently working towards a translation of the books into English, to share the stories to a wider audience.

Volume One, ‘Les Femmes dans les Nuages, Aéronautes, Parachutises, Aviatrics 1784-1918’ is available now in hardback.

Volume Two, ‘Les Femmes dans les Nuages, Aéronautes, Parachutises, Aviatrics 1918-1945’ is available on pre-sale, for publication in December 2023.

Photograph and article: Caitlin Smith, FAI Web Editor